Microservices Security

Note: If this is your first time hearing about OAuth 2.0 or you want to get familiar with the grant types we are using, please read this article first.

Everyone’s excited about microservices, but the actual implementation is sparse. Perhaps the reason is that people are unclear on how these services talk to one another. The most tricky thing is access management throughout a sea of independent services.

While designing microservices, a big monolithic application is broken down into smaller services that can be independently developed and deployed. The final application will have more HTTP calls than a single monolithic application, how can we protect these calls between services?

To protect APIs/services, the answer is OAuth 2.0, and the most simple and popular solution will be a simple web token as an access token. The client authenticates itself on OAuth 2.0 server and OAuth server issues a simple web token (a UUID in most of the cases), then the client sends the request to API server with access token in the Authorization header. Once the API server receives the request, it has to send the access token to OAuth server to verify if this is a valid token and if this token is allowed to access this API. As you can see, there must be a database lookup on OAuth server to do that. Distributed cache helps a lot, but there is still a network call and lookup for every single request. OAuth server eventually becomes a bottleneck and a single point of failure. For more details on why Simple Web Token is not suitable for microservices architecture, please refer to swt vs jwt.

Years ago, when JWT draft specification was out, I came up with the idea to do the distributed security verification with JWT to replace Simple Web Token for one of the big banks in Canada. At that time, there was nobody using JWT this way, and the bank sent the design to Paul Madson and John Bradley who are the Authors of OAuth 2.0 and JWT specifications and got their endorsements to use JWT this way.

Requirement

Different organizations have different security requirements. When designing the security architecture of Light, we have to make sure that it is suitable for all types of organizations. In most cases, security is a tradeoff between performance and risk. If you build a blog application, you want it to be as fast as possible with adequate security. If you are building a banking application, you want it to be as secure as possible. So we cannot have one security design for all customers. We need to have multi-tier of security ranged from low, medium and high. In the next section, we list all the use cases in the consideration.

Beside above requirements, we need to ensure that interactions to the OAuth 2.0 provide is miniume so that we can save network hops.

Another requirement is to follow OAuth 2.0 flow as much as possible. Only extend it if absolute possible.

Use Cases

Traditional Web Service

Traditional Web Service is flattened and typically only used within the internal network. If it is exposed to the internet, an API gateway is used for security. As this is the use case addressed in the OAuth 2.0 specification, authorization code or client credentials flow are used with only one access token in the Authorization header.

Microservice to Microservice

When an original client calls the first microservice, it only passes one token in the Authorization header. That token can be the authorization code token or the client credentials token. When the first microservice calls another one, the original token is still passed in the Authorization header to the next service; however, the original token won’t have the right scope.

Standalone App to Microservices

Standalone applications like desktop applications or batch jobs might not have a specific user info but will need to access API or services to fulfill its task. In this case, the client credentials grant type will be followed.

Single Page App to Microservices

Native Mobile App to Microservices

Design Principal

OAuth 2.0 is the de facto standard for API security, and we are following it as closely as possible. However, OAuth 2.0 was written for web services, not microservices, and there is no coverage for service to service invocation. The solution is to add more functionalities when OAuth 2.0 is not enough.

Distributed JWT Verification

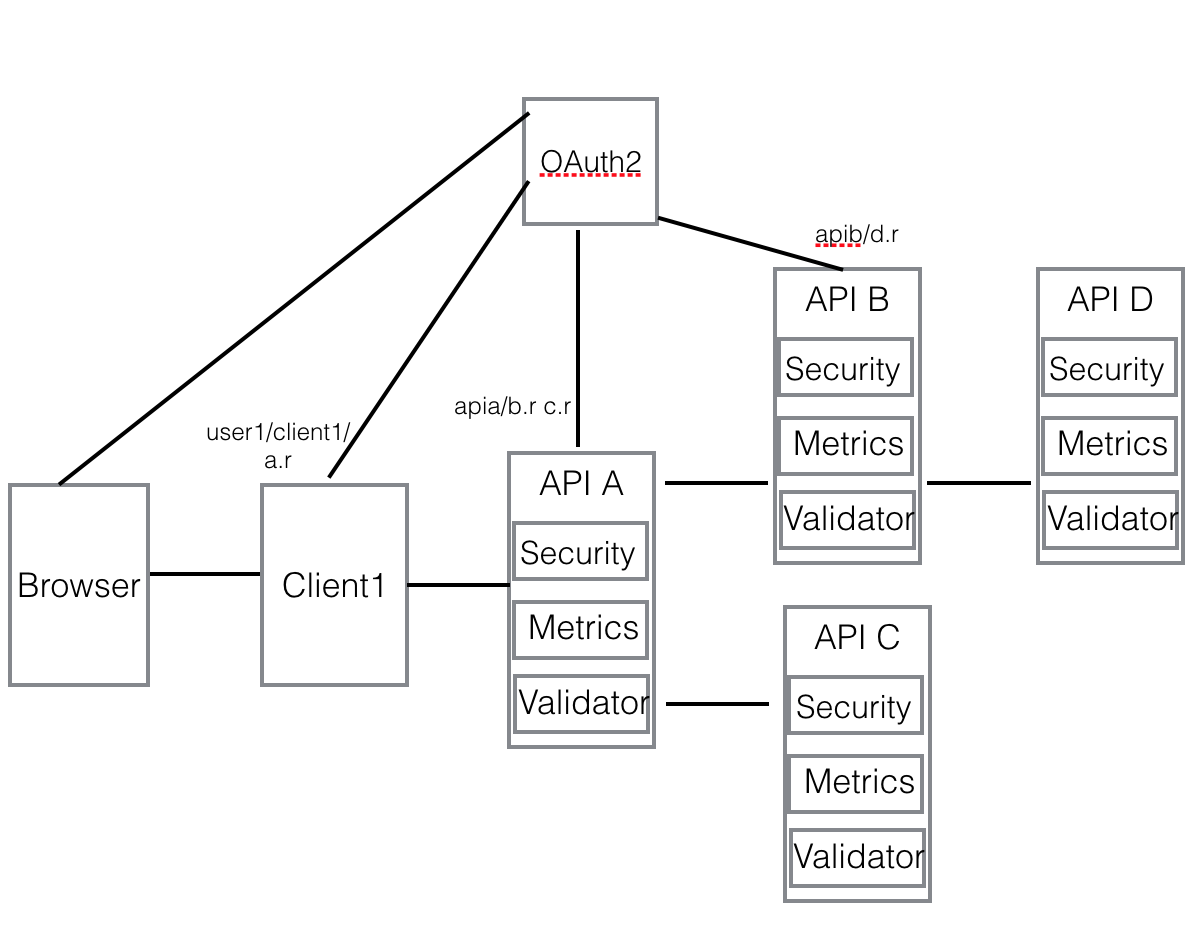

Here is the diagram of distributed JWT verification for microservices.

Let’s assume the following:

- Client1 is a web server, and it has client1 as client_id.

- API A is a microservice, and it has apia as client_id, and it requires a.r scope to access.

- API B is a microservice, and it has apib as client_id, and it requires b.r scope to access.

- API C is a microservice, and it has apic as client_id, and it requires c.r scope to access.

- API D is a microservice, and it has apid as client_id, and it requires d.r scope to access.

User trigger the authentication

When a user clicks the login button or accesses a resource that is protected, he/she will be redirected to OAuth 2.0 server to authenticate. After input username and password, an authorization code is redirected back to the browser. The client1 will handle the redirect url and get the authorization code. By sending client1 as client_id, client_secret and authorization code from user to OAuth server, Client1 gets a JWT token with

- user_id = user1

- client_id = client1

- scope = [a.r]

This token will be put into the Authorization header of the request to API A. When API A receives the request, it verifies the JWT token with the public key issued by OAuth server with the security middleware handler in the framework. If the signature verification is successful, it will verify the scope in the token against the OpenAPI specification defined for the endpoint Client1 is accessing. As a.r is required and it is in the JWT scope, it allows the access.

API A calls API B and API C

Now API A needs to call API B and API C to fulfill the request. As this is API to API call or service to service call, there is no user ID involved and Client Credentials flow will be used here to get another JWT token to access B and C. The original JWT token doesn’t have the scopes to access B and C as Client1 does not even care A is calling B and C. So here API A needs to get a token associated with client_id apia which has the proper scope to access API B and API C.

This token will have the following claims.

- client_id = apia

- scope = [b.r c.r]

As the original token has the original user_id or custom claims, it is carried in the entire service to service calls in the Authorization header so that each service has a chance to do fine-grained (role-based or user-based) authorization if it is necessary. The new client_credentials token will be passed in the request header “X-Scope-Token” for scope verification against OpenAPI specification on API B and API C.

API B and API C token verification

The token verification on API B and API C are the same. So let’s use API B as an example to explain the verification process.

When API B receives the request, it first checks the Authorization token to make sure it is valid for signature verification. Then if scope verification is enabled, it checks if ‘X-Scope-Token’ header exists. If yes, it will verify its signature and match the scopes with endpoint defined scopes in the specification. If scope matching is failed, it will fall back to Authorization token to see if it has the scopes required. If none of the tokens has the scopes required, an error will be sent back to the caller.

API B calls API D

The process is very similar to API A calls API B and API C. A client credentials token will be retrieved by API B from OAuth server, and it has the following claims.

- client_id = apib

- scope = [d.r]

API D token verification

Similar to API B and API C token verification.

Token Exchange and Token Chaining

As described above, there are two tokens involved for service to service invocation and this pattern should cover most of the security requirement. However, there are certain cases that verify only the immediate caller is not enough. For example, the payment service needs to know that the request is initiated from the shopping cart and go through the order service. This cannot be done with the above two token pattern. In order to verify the call stack, the access/scope token must be chained so that the entire call stack can be verified by any token in the chain.

OAuth 2.0 has a draft specification called token exchange and it can be utilized to embed previous token client id in the current token client id. In this case, when service goes to OAuth server to get the token, it must pass the access token it has received to the OAuth server so that the client id can be chained together in the new token. When the target service receives the token, it can verify the call stack in the token against its configuration to decide if access can be granted.

Client Credentials / Scope Token Cache

As described above, for every API to API call, the caller must pass in a scope token in addition to the original token. Unlike the original token which is associated with a user, the scope token is only associated with a client (API / service) and it will only expire after a period configured on OAuth server. So it is not necessary to get the new scope token for every API to API call. The token is retrieved and cached in memory until it is about to be expired then a new token will be retrieved.

The entire token renew process is managed by Client module provided in the light-4j framework. This client module encapsulates a lot of features to help API to API calls.

Authorization Token Cache

The original token normally will be cached in the web server session so that the subsequent calls from the same user can use the cached token. The JWT token should not be sent to the browser as it is not trusted.

Single Sign On

As the end user login is managed by OAuth server, there is a session established between user’s browser and OAuth server. When the user switches to another tab on his/her browser to access another application, the login on OAuth is not necessary, and a new authorization code will be immediately redirected back.

Fine-Grained Authorization

Above authorization is based on the client_id and the scopes in the JWT token and it can be verified by JwtVerifierHandler without any context information regarding a specific API endpoint. And it can be applied blindly as a technical middleware handler at the framework level. For other fine-grained authorizations, they must be applied based on the business context of the service, and normally each organization will have their customized middleware handler to address the concern depending on the nature of the business. The following are three examples commonly used.

Role-Based

Role-Based authorization must be specific to one or a group of services with a set of pre-defined roles. Normally the role can be embedded into the Id token and the mapping should be cached in the handler.

Attribute-Based

For example, only an account manager can access an account, or an employee based on one geolocation can access customers based on the same geolocation.

Rule-Based

Teller can only transfer money less than $10,000.00 etc, and his/her manager can override the rule with manager’s token.

Request and Response Filter

Sometimes, certain request fields need to be removed based on the clientId or other attributes so that the rule business handler can be done in a consistent way. Also, for certain clients or users, the response might need to filter out some information before returning to the consumer.

JWT public key certificate distribution

As we are using JWT token for distributed token verification on each service instance, we need to make sure that the public key certificate from OAuth 2.0 provider can be distributed to each individual service instance so that they can verify the token issued by the same OAuth 2.0 token service independently.

Here is the document that describes how the key is distributed to the services during bootstrap and key rotation at the runtime.